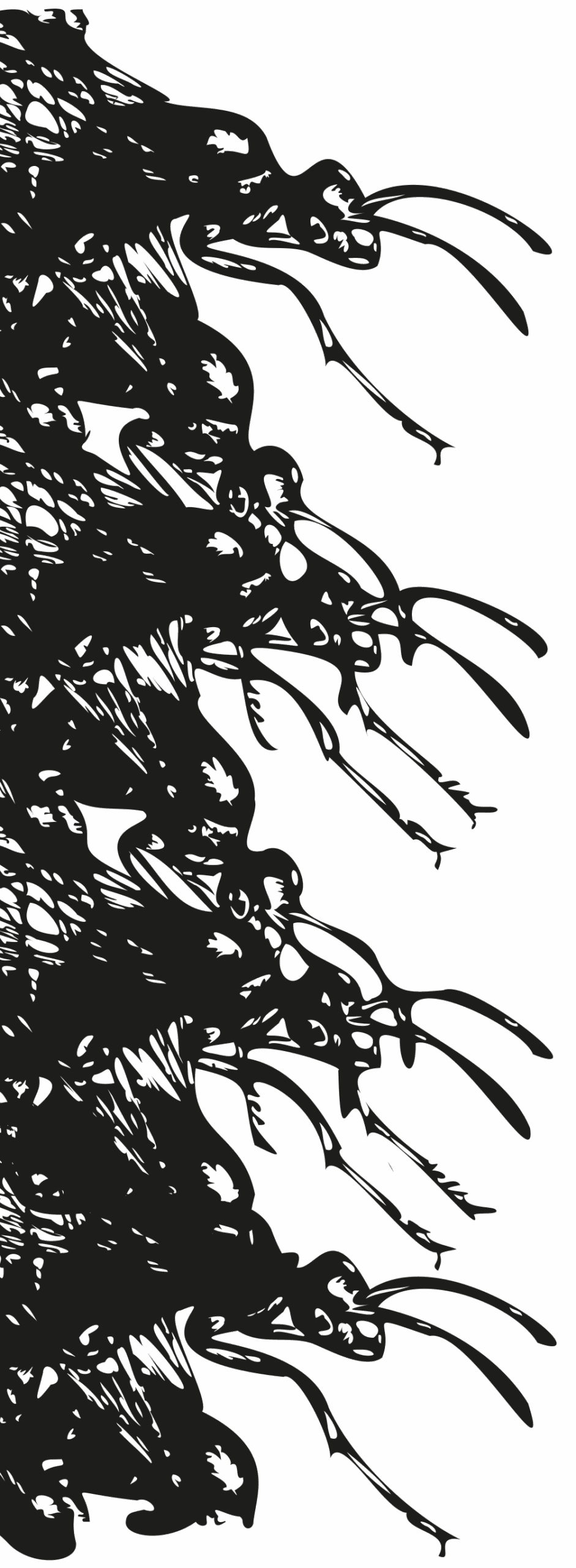

Millions of bodies, one mind. An outlook on the organizational prowess of insectoid societies.Millions of bodies, one mind. An outlook on the organizational prowess of insectoid societies.

Millions of bodies, one mind. An outlook on the organizational prowess of insectoid societies.Millions of bodies, one mind. An outlook on the organizational prowess of insectoid societies.

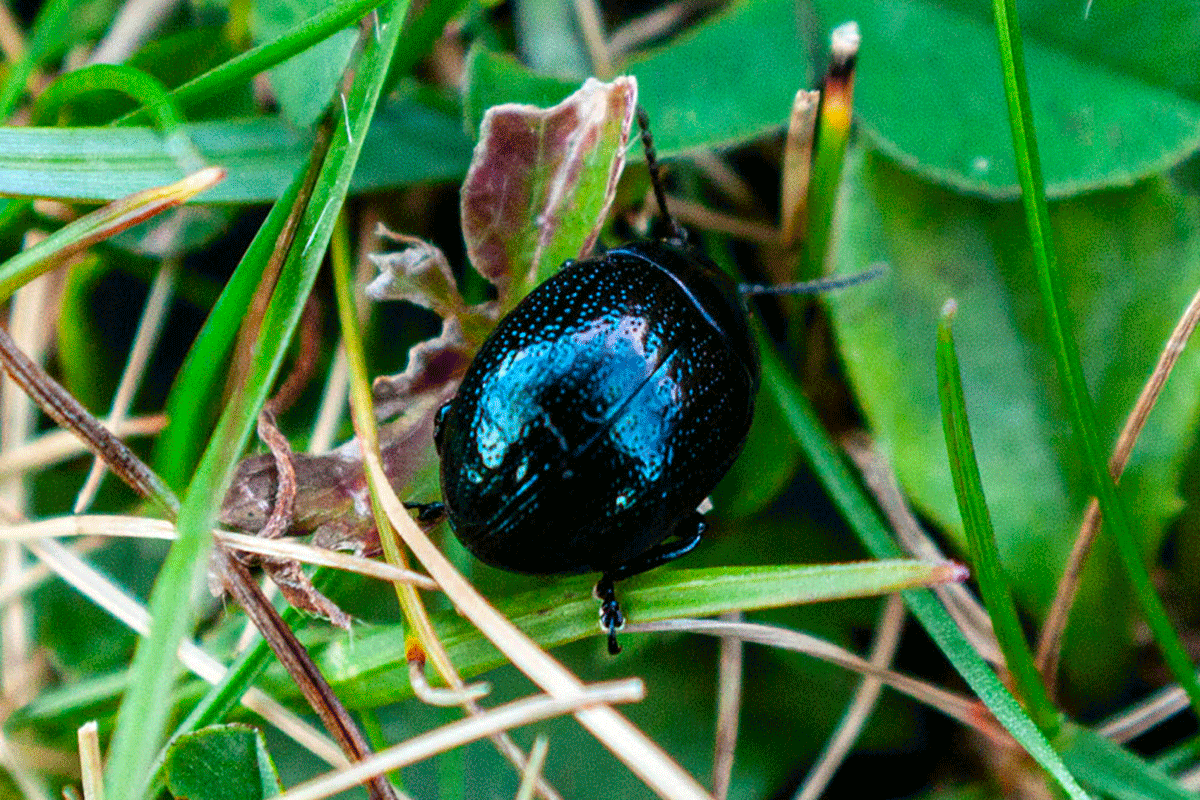

The concept of the hive mind is most easily applied to insects such as bees or ants. It’s the group intelligence that emerges when these species work as only a unit. Toker D. The emergence of the hive minds: Should we worry? Knowing all of the other Neurons. But there are many other examples in which human intelligence makes up a hive mind. In popular culture it’s often also portrayed as bad thing. But why should it be a bad thing when it has demonstrated countless times how beneficial for survival it is?

Makes you think, what would happen to us in a shared consciousness? How would we function as a conjoint entity? What would happen to emotions? Feelings? Relations? There is in the deed some thing strangely comforting about the idea of a hive mind.

In insect societies, we think it reveals itself out of ego or ambition when it’s really about survival through coordination. No lone decision-making or hesitation, but a collective rhythm that keeps everything moving. Everyone just knows what to do, and somehow, it works as if it was that easy. It makes you think about how humans chase individuality like it’s sacred, while ants and bees have been thriving for millions of years by doing the opposite. Maybe the hive mind isn’t about losing yourself — maybe it’s about trusting the system, trusting that the bigger pattern knows way more than you will ever do in this life or in any actual.

It is fair and easy to yes romanticize that unity until you do remember: these hives don’t debate, they act. There’s no “ maybe ” in them swarms. Just never ending motion. And well yes maybe that is what fascinates us — the fantasy of not having to think so hard. Of being carried by a collective pulse instead of our own endless overthinking. There’s a kind of peace in that, even if it’s mostly mechanical.

Deja tu comentario